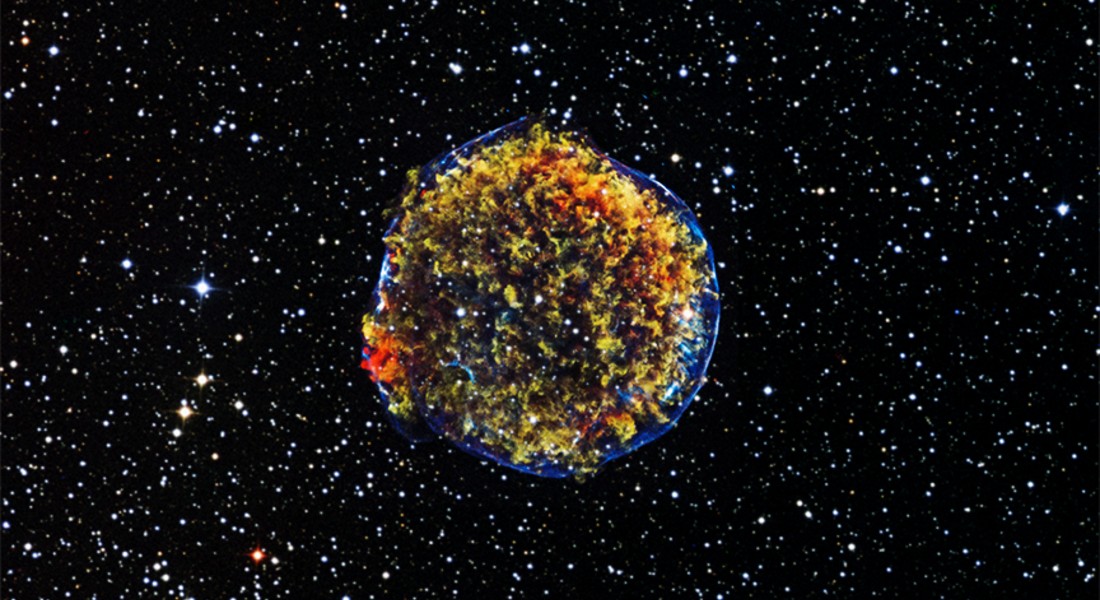

Until now, researchers have believed that dark energy accounted for nearly 70 percent of the ever-accelerating, expanding universe. For many years, this mechanism has been associated with the so-called cosmological constant, developed by Einstein in 1917, that refers to an unknown repellant cosmic power.

But because the cosmological constant—known as dark energy—cannot be measured directly, numerous researchers, including Einstein, have doubted its existence—without being able to suggest a viable alternative.

Until now. In a new study by researchers at the University of Copenhagen, a model was tested that replaces dark energy with a dark matter in the form of magnetic forces.

“If what we discovered is accurate, it would upend our belief that what we thought made up 70 percent of the universe does not actually exist. We have removed dark energy from the equation and added in a few more properties for dark matter. This appears to have the same effect upon the universe’s expansion as dark energy,” explains Steen Harle Hansen, an associate professor at the Niels Bohr Institute’s DARK Cosmology Centre.

The universe expands no differently without dark energy

The usual understanding of how the universe’s energy is distributed is that it consists of five percent normal matter, 25 percent dark matter and 70 percent dark energy.

In the UCPH researchers’ new model, the 25 percent share of dark matter is accorded special qualities that make the 70 percent of dark energy redundant.

“We don’t know much about dark matter other than that it is a heavy and slow particle. But then we wondered—what if dark matter had some quality that was analogous to magnetism in it? We know that as normal particles move around, they create magnetism. And, magnets attract or repel other magnets—so what if that’s what’s going on in the universe? That this constant expansion of dark matter is occurring thanks to some sort of magnetic force?” asks Steen Hansen.

Computer model tests dark matter with a type of magnetic energy

Hansen’s question served as the foundation for the new computer model, where researchers included everything that they know about the universe—including gravity, the speed of the universe’s expansion and X, the unknown force that expands the universe.

“We developed a model that worked from the assumption that dark matter particles have a type of magnetic force and investigated what effect this force would have on the universe. It turns out that it would have exactly the same effect on the speed of the university’s expansion as we know from dark energy,” explains Steen Hansen.

However, there remains much about this mechanism that has yet to be understood by the researchers. And it all needs to be checked in better models that take more factors into consideration. As Hansen puts it:

“Honestly, our discovery may just be a coincidence. But if it isn’t, it is truly incredible. It would change our understanding of the universe’s composition and why it is expanding. As far as our current knowledge, our ideas about dark matter with a type of magnetic force and the idea about dark energy are equally wild. Only more detailed observations will determine which of these models is the more realistic. So, it will be incredibly exciting to retest our result.

Contact:

SCIENCE Communicationnyhedsteam@science.ku.dk

Tel: +45 Tel. +45 35 33 28 28

from ScienceBlog.com https://ift.tt/3mg4hiI

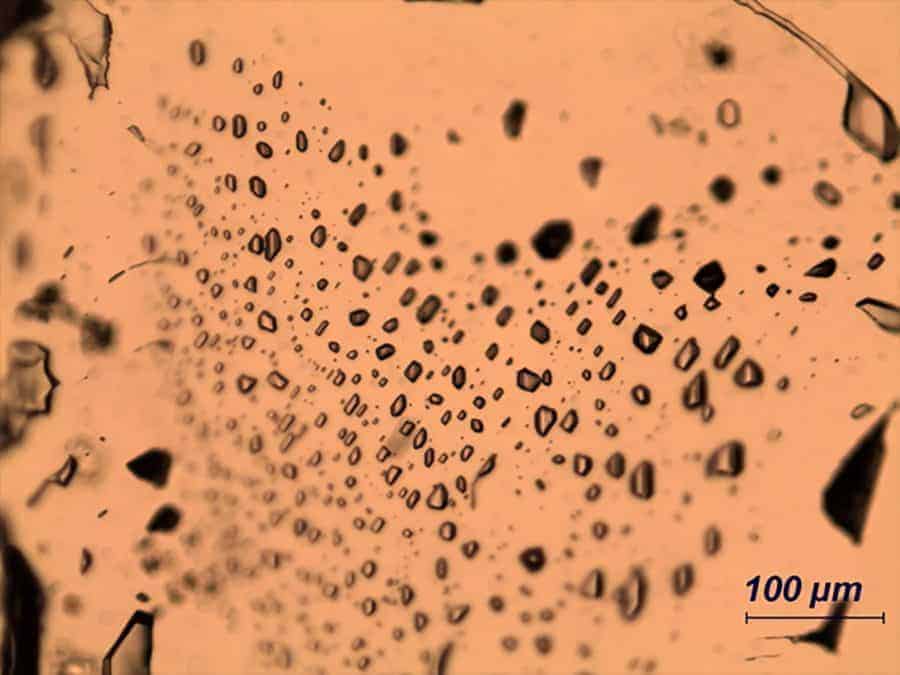

, tools that allow researchers to pinpoint high viral gene expression within tumor tissue but not in surrounding healthy tissue.

, tools that allow researchers to pinpoint high viral gene expression within tumor tissue but not in surrounding healthy tissue.