Antioxidants proved a bust for life extension almost 25 years ago, but glutathione stands out as an exception. We lose glutathione as we age, and supplementing to increase glutathione levels has multiple benefits, possibly on lifespan.

Glutathione is manufactured in the body via an ancient mechanism taking as input cysteine, glutamic acid, and glycine. Supplementing N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) and glycine are independently associated with health benefits, and possibly increased lifespan. Glutamine seems to be in adequate supply for most of us.

Each cell manufactures its own glutathione. (GSH is an abbreviation for the reduced form of glutathione.) Concentrations of GSH within a cell a typically 1,000-fold higher than in blood plasma. When we look for glutathione deficiency, we measure the blood level, because that is convenient. It is much harder to measure intracellular levels of GSH. These two studies [2011, 2013] demonstrated that intracellular levels decline with age more consistently and more severely than blood levels. People in their 70s have less than ¼ the glutathione (in red blood cells) that they had when they were in their 20s. The same study also found that intracellular levels of cysteine and glycine but not glutamate decline with age.

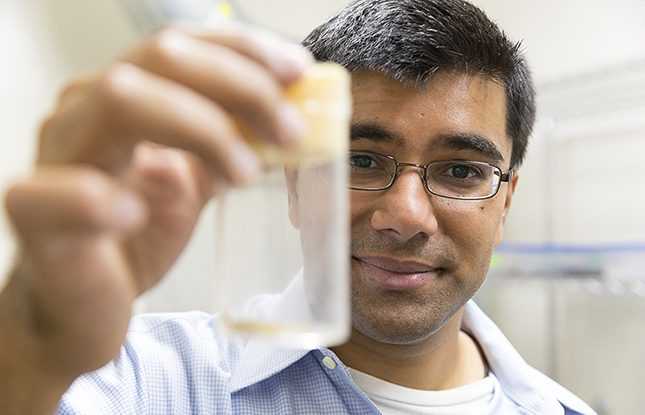

Supplementing with NAC is already known to boost glutathione levels. But here is a motivation to try a combination of glycine and NAC, dubbed “GlyNAC” to see if we can do even better. This work has been spearheaded by Rajagopal Sekhar.

In humans, “Supplementing GlyNAC for a short duration of 2 wk corrected the intracellular deficiency of glycine and cysteine, restored intracellular GSH synthesis, corrected intracellular GSH deficiency, lowered OxS, improved MFO, and lowered insulin resistance.” [Sekhar] Most of these benefits are theoretical. Lowering oxidation levels is a double-edged sword. MFO=mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, and this benefit is on firmer footing. Membranes are made of fatty acids, and mitochondrial efficiency, like most everything in the body, depends on highly selective membranes. The crowning benefit is improved insulin sensitivity, and we can be fairly confident this leads to longer healthspan.

The two recent studies, in humans and mice, are indeed impressive.

The small human study found that “GlyNAC supplementation for 24 weeks in OA corrected RBC-GSH deficiency, OxS, and mitochondrial dysfunction; and improved inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, insulin-resistance, genomic-damage, cognition, strength, gait-speed, and exercise capacity; and lowered body-fat and waist-circumference.” Though they didn’t measure methylation age, this constellation of improvements gives us confidence that people were looking and acting younger.

In older (71-80 yo) subjects 24 weeks of GlyNAC supplementation raised intracellular GSH levels from 0.4 mmol to 1.2, compared to 1.8 in young adults. (Levels were measured in red blood cells.)

Two central players in aging are inflammation and insulin resistance; both showed excellent response.

Inflammation decreased markedly: Average C-reactive protein (CRP) dropped from 4.9 to 3.2 (compared to 2.4 for young people). IL-6 dropped from 4.8 to 1.1 (ref 0.5 for young). TNFα dropped from 98 to 59 (ref 45).

Insulin resistance fell just as dramatically, along with fasting glucose and plasma insulin.

Cognitive performance improved markedly! as did grip strength, endurance, and gait speed.

GlyNAC subjects lost a lot of weight — 9% of body weight in 24 weeks. This is both very good news and a hint that some of the benefits of GlyNAC may be caloric restriction mimetic effects, indirectly due to suppression of appetite or of food absorption.

Is all this evidence of a decrease in biological age?

But the effects faded weeks after the treatment stopped. This, I believe, is different from resetting methylation age. There is not a lot of data yet to test this, but I believe that methylation is close to the source of aging; in other words, the body senses its age by its epigenetic state, and adjusts repair and protection levels accordingly. Thus changing epigenetics to a younger state, IMO, effectively induces an age change in the body.

If this is correct, then my guess is that GlyNAC does not set back methylation age, based on the fact that the effects must be continually renewed by daily doses of glycine and NAC. On the other hand, mitochondria are such a central player in expressing multiple symptoms of aging that it may well be that continuous treatment with GlyNAC leads to longer lifespan.

…and indeed that is what was just reported in a mouse study. 16 mice lived 24% longer with GlyNAC supplementation, compared to 16 controls. 24% is impressive (see table below). For example, rapamycin made headlines a decade ago with an average lifespan increase of 14%. (In other studies, rapamycin was associated with even greater life extension.) The winner in this table is a Russian pineal peptide, which claims 31% increase in lifespan. I have previously bemoaned the fact that this eye-popping work from the St Petersburg laboratories of Anisimov and Khavinson has not been replicated in the West (though Russian peptides are now commercialized in he West).

Table source: https://ift.tt/uB6TMaU

(This is a sample — not a complete list.)

| Treatment | Lifespan increase |

| Epithalamin | 31% |

| Thymus Peptide | 28% |

| Rapamycin | 26% |

| N-Acetylcysteine | 24% |

| GlyNAC 2022 | 24% |

| Spermidine | 24% |

| Acarbose | 22% |

| Phenformin | 21% |

| Ethoxyquin | 20% |

| Vanadyl sulfate | 12% |

| Aspirin | 8% |

An asterisk must be placed next to the new 24% life extension from GlyNAC. Eleven years ago, Flurkey, found the same 24% life extension with NAC alone. NAC supplementation without glycine is known to increase glutathione production. Do we need glycine in addition, or is cysteine the bottleneck? Levels of both free glycine and cysteine decline with age. This would suggest that supplementation of both should be more effective than supplementing NAC alone. But I was unable to find any study that asked whether GSH levels are raised to a greater extent by GlyNAC than by NAC alone.

Glycine supplementation in large amounts mimics methionine restriction, which is a known but impractical life extension strategy.

If you decide to take glycine, it should be at bedtime, and in large amounts, a teaspoon or two. (I did this for awhile using glycine as a sweetener in hot chocolate soymilk, until I decided it ruined the taste of the chocolate drink. Whether this is a sound reason for tailoring an anti-aging agenda I’ll leave you to decide.)

All this work comes out of the laboratory of Rajagopal V. Sekhar at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas. It’s time that a broader life extension community joined in the action. I’m grateful to Dr Sekhar for commenting on earlier drafts of this article.

from ScienceBlog.com https://ift.tt/feCOmpW