Scientific publications can serve as key evidence to policymakers, as well as provide possible discussion points to inform public debate. For example, comprehensive, systematic reviews of literature regularly influence recommendations such as medical guidelines when it comes to public health policy around major issues such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The growing number of preprints available should in theory provide a faster, albeit less reviewed mechanism for researchers to share their work during the pandemic. However, what this entails is that the means to meddle with scientific communications are that much more available. But what would motivate a person, group of people, or even an organisation to intentionally game the scientific system? Personal, professional, or political – the motivations exist within people who want fame and fortune to fast-track their ambitions. Whether they use fair means or foul.

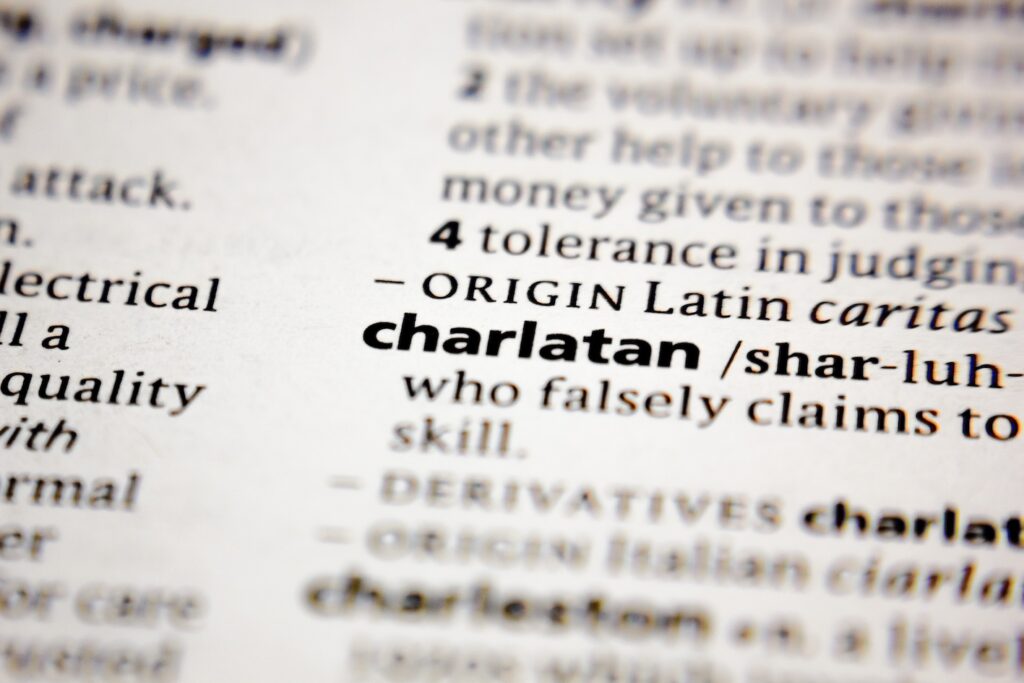

Charlatans in science are sadly not new. Persons making grandiose claims about their knowledge and outrageous cures for diseases have peppered medical history for centuries. With charismatic personalities and opportunities to influence, such individuals have professed false cures in the house of Tsar Nicholas (Rasputin) and misled ailing Londoners during an epidemic (Gustavus). Charmers playing by their own rules – gaslighting others.

Even in the least nefarious circumstances, lone actors can emerge to try to falsify science. Immense pressures placed on scientists to conduct research, publish results and have those results cited would tempt anyone to search for shortcuts. Researchers are humans, after all. Implement these requirements in an environment that supports gamifying just about anything, and even the most honest person could fail under the pressure that’s exerted.

In one case where citations were required for someone’s work, a researcher created fictitious authors in plagiarized papers to cite that work. Their work, in fact. Dr Yibin Lin posted six papers and attempted to submit eight more to preprint servers (see one example here). The case of attempting to accelerate promotion resulted in a 10-year ban from scientific research within the US.

In other cases, the motivations can only be understood from the people themselves, for example those individuals who fake being scientists. There is a long history of people outside of science providing advice as if they were experts. Some amazing citizen scientists exist, but the signal-to-noise ratio favours chaos more than substance.

There are parallels with predatory journals and those who publish their articles in them. In her seminal article on the motivations of authors published in such journals, Tove Faber Frandsen identified two main groups – the unaware and the unethical. The former claim to be ignorant of the existence of predatory journals, and innocent in succumbing to the tried and tested tactics of predatory publishers, the latter, on the other hand, exploit their existence to ensure publications – sometimes to ensure they reap the incentives in place for them, sometimes to publish unsubstantiated research. Most clearly, this has occurred during the pandemic with everything from 5G conspiracy theories to the promotion of debunked drugs and therapies appearing in fake journals.

As harmless as acting alone may seem in such an expansive scientific ecosystem, the consequences of a lone wolf pale in comparison to targeted attacks. Science mercenaries, well-funded by and coordinated with varying industries, can intentionally fracture the confidence in a topic. Seitz and Sanger – trained physicists later hired to undermine the harms of tobacco and climate change – worked on the atomic bomb and had legitimate education and training as physicists. As described in depth in the Merchants of Doubt the two scientists would eventually testify in court as if they were experts in epidemiology, environmental science, virology, and dozens of other areas to undermine the confidence of overwhelming scientific evidence in the harm of tobacco and the impact of climate change. They are not alone. A whole industry exists to profit from undermining science. Worried that second-hand smoke may kill your industry? The answer seems to be to kill the research by overwhelming the regulatory agencies and polluting the scientific literature.

“Countering nefarious acts and actors must be coordinated throughout the scholarly community – publishers, institutions, and funding agencies, to name a few. Policies and practice must move from the current defensive, reactive position, to the offensive.”

Leslie McIntosh, CEO, RIPETA

As with other pandemics, we have seen a plethora of charlatans emerge during the COVID-19 pandemic. From the MBAs who would ‘set the record straight on COVID’ to the self-proclaimed experts on COVID and policy. To illustrate one scam: a scientific piece would be written, typically with one author having credentials in a scientific field. The co-authors either do not exist (e.g. Yan report) or do not have supporting credentials (e.g. research conducted by Walach). In some cases, the ‘papers’ appear in repositories with little proofing evident. In other cases, the work gets published in ostensibly peer-reviewed journals – meaning the peer review, if it happened at all, was not rigorous, such as those articles published in predatory journals. Success in the eyes of the authors would see a scientific social media outcry happen where someone eventually shreds the methodology. But the authors have won. It’s a misinformation strategy: i) Put out bad-faith information on Topic X; ii) Methodology of Topic X is deeply refuted; iii) Topic X is discussed; iv) Words of Topic X are propagated. Win for the bad-faith actors.

This would be like writing an article: Squirrels – Wonderful Companions in the Garden. As everyone knows, evil squirrels steal tomatoes from the garden and throw acorns from trees maliciously trying to deprive the owners of any peace. Cute con artists at best. The authors’ intent would be to spread the lie of the delightful aspects of squirrels – intentionally putting in the key phrase they want propagated in the article title. So when a social media argument ensues, and good scientists cite the title as-is and the bad-faith actor’s message sticks: squirrels are lovely garden mates. And the lie spreads – because we as scientists playing by scientific rules indulge in critiquing the methodology before deciding on the legitimacy of the source. We legitimize their argument.

An individual infiltrating published science with falsehoods still pollutes the ecosystem. But the motivation to put profit over protecting society causes harm at scale. In the end, the tactics of the few will overpower an ecosystem lacking a robust strategy.

Countering nefarious acts and actors must be coordinated throughout the scholarly community – publishers, institutions, and funding agencies, to name a few. Policies and practice must move from the current defensive, reactive position, to the offensive – taking proactive measures to prevent harmful players entering the ecosystem and promoting automated quality checks that scale with the pace of scholarly communication.

For more information about how Ripeta can help make better science easier – for publishers, funders, researchers and academic institutions – please visit the Ripeta website.

About the Author

Dr Leslie McIntosh, CEO | Ripeta

Dr McIntosh is the founder and CEO of Ripeta, a company formed to improve scientific research quality and reproducibility. Part of Digital Science, Ripeta leads efforts in automating quality checks of research manuscripts. Academic turned entrepreneur, Dr McIntosh served as the executive director for the Research Data Alliance (RDA) – US region and as the Director of the Center for Biomedical Informatics at Washington University School in St. Louis. Over the past years, she has dedicated her work to improving science.

The post Motivations of Bad Actors in Science: The Personal, The Professional, The Political appeared first on Digital Science.

from Digital Science https://ift.tt/GjFsZLo