Unravelling the academic impact of 007

On the 70th anniversary of the publication of Ian Fleming’s first James Bond novel, Casino Royale, we ask the question: Why does James Bond have such a large footprint in scholarly literature? Our analysis reveals that Bond, James Bond, is about more than just espionage, vodka martinis and cinema studies.

Every so often a fictional character is so well drawn that even though they often embody the ideals or sensibilities of a non-contemporary era, with all the challenges that can present, they transcend their original zeitgeist to be constantly reinvented, renewed and, to use a modern term, rebooted for new generations.

In science fiction and fantasy, this is a familiar trope, with Doctor Who, Superman and Spider-Man all being prime examples of characters who receive frequent updates for contemporary audiences. Outside science fiction, you will be hard put to call to mind a character with the same enduring appeal and knack for self-reinvention.

The almost sole example of such a character is one Commander James Bond of the British Secret Service – a character who so thoroughly embodies Britishness (even Englishness) of a certain style and period that it is almost at odds with his seeming longevity. And yet, this month he celebrates 70 years since first jumping off the page of Casino Royale, Ian Fleming’s 1953 novel that introduced the world to the suave sophistication of Cold War international espionage.

This first novel introduced readers to Bond’s car, a 1930 Blower Bentley (it was not until Fleming’s 1959 novel Goldfinger that Bond gets an Aston Martin DB Mark III), the .25 Beretta (the Walther PPK was introduced in the novel Dr No in 1958), and the Vesper Martini (a vodka martini of the shaken rather than stirred variety that Fleming invented and named for Bond’s love interest Vesper Lynd).

Despite the challenges of Bond’s originally written misogyny, and references to race that the publisher says are being revised, he has become much loved around the world, and lays claim to one the most successful film franchises in the history of cinema. A major cultural export for the UK, Bond films have featured and established icons of the British music scene including singer Dame Shirley Bassey and composer John Barry. In addition, the films highlighted both British and non-British brands while pioneering brand positioning in movies while, at the same time, making Q (no, not the one from Star Trek) a household name.

Bond has come to embody a certain brand of Britishness, a fact clearly acknowledged as Daniel Craig was chosen to appear as Bond to escort Her Majesty the Queen to the London Olympics in a short film prepared for the 2012 opening ceremony. And, as life sometimes imitates art, (and perhaps also gives an insight into the wry sense of humour of a particular member of the Royal family), a decade later Daniel Craig was awarded a CMG (the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George) in recognition of his services to theatre and cinema in the Queen’s 2022 Birthday Honours – the same honour given to the fictional Bond by Fleming in 1957’s book, From Russia with Love.

Thousands of scholarly articles have been written about James Bond since his inception – but how do we know this, and what are they about?

A simple Dimensions search limited to titles and abstracts yields 674 references to James Bond, including the descriptively titled 2022 article “No Mr Bond, we expected you to die”: a medical and psychotherapeutic analysis of trauma depiction in the James Bond films, and A Psychological Study of the Modern Hero: The Case of James Bond. Arguably these articles represent those where Bond is a central focus of the work, but even at this level, a quick look at the ANZSRC article classifications (recently updated to the new ANZSRC Field of Research (FoR) 2020 codes as described in our recent paper) is revealing, with work being classified as code 36 – Creative Arts and Writing (with 3605 – Screen and Digital Media accounting for much of the 2-digit-level assignment) only accounting for around 30% of research output. Even though Bond has made his mark beyond the creative arts, Bond-themed titles do appear to be more predictable (compare, for example, 2009’s “Compute? No, Mr. Bond, I Expect You to Die!” with our earlier-mentioned paper).

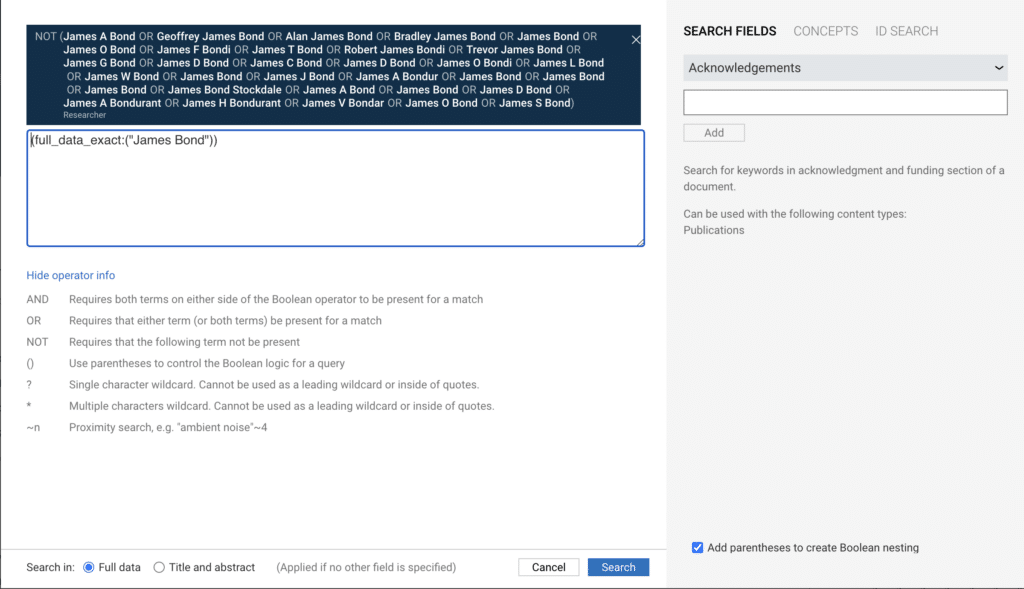

Using Dimensions’ advanced searching capabilities, we quickly find that James Bond’s impact on research discourse is much larger than this apparently meagre 600 articles from the basic search above. If we broaden the search to use Dimensions’ Exact Search (one of the advanced search tools that allows more powerful, fine-grained searches of the full-text corpus behind Dimensions), then we can identify more than 28,000 articles that mention James Bond. Of course, this more advanced search includes full text, and hence we need to be more careful with our methodology. In this case, the query needs to be modified to remove all 32 authors who are fortunate (or indeed unfortunate) enough to have the name James Bond contained within their names.

In this expanded dataset, references to Bond can be more tangential – for example, as a cultural reference: Bond as a relatable example, a gateway or a framing for a set of ideas, or to quickly orient the reader to a specific era, or a set of values. Indeed, in this expanded dataset, ANZSRC FoR code 36 – Creative Arts and Writing – is no longer the dominant category, with code 47 – Language, Communication and Culture – taking the top spot.

However, even this new dominant category only occupies 12% of the “Bondverse”, with a much greater diversity of topics playing a role, including FoR 44 – Human Society with 7.7%, 43 – History, Heritage and Archaeology 4.0%, 35 – Commerce, Management, Tourism and Services 3.7%, and 46 – Information and Computing Sciences at 3.5%. Indeed, articles in the Bondverse have been written on Gender Studies, Built Environment and Design, Political Science, Philosophy and Religion, Psychology, Marketing, Biomedical Sciences and Law, all of which are able to use James Bond as a gateway to help people relate to their topic.

The brand of Bond is so powerful that it is often mentioned through other affiliations, such as those with particular artists as in “Man vs the machine: The Struggle for Effective Text Anonymisation in the Age of Large Language Models”, where singer/songwriter Adele is the principal focus of the commentary, but where Bond receives a collateral mention; or where Bond’s connection to those wonderful gadgets and cars from the long-suffering Q means that he is a natural point of reference as in Automated Driving in Its Social, Historical and Cultural Contexts. Each year, a consistent 1000 or so articles refer to James Bond (approximately the output of a medium-sized research institution). Outlets that regularly publish articles referring to James Bond include SSRN, the Journal of Cold War Studies (MIT Press Direct), Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Springer Nature), The Historian (Taylor & Francis Online) and Nature. It is perhaps of little (Quantum of?) solace to the Journal of British Cinema and Television and Film Quarterly that they are some way down the list.

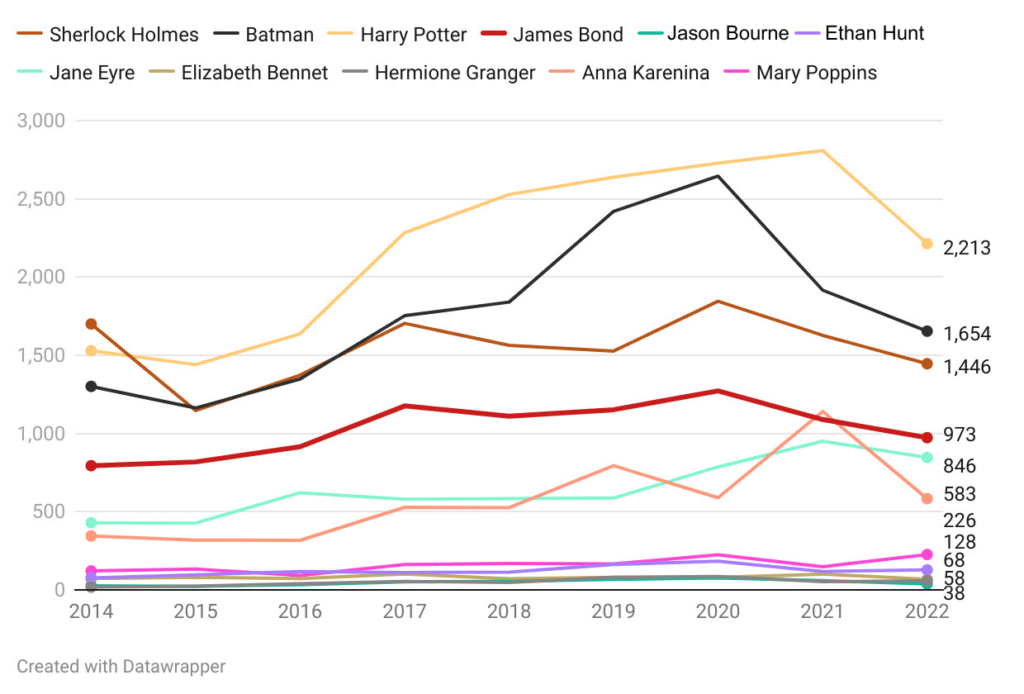

Of course, Bond is not alone as a fictional figure who has made his mark in the research literature, there are other prominent fictional characters that we use as a shorthand for cultural references. James Bond fares well in these stakes, beating most recent characters such as Ethan Hunt from the Mission: Impossible franchise, and Jason Bourne. But he has not yet attained the same level of cultural embeddedness as more established figures such as Sherlock Holmes (who even has his own adjectival form, “Holmesian”), Batman (for which our analysis, perhaps unfairly, also includes mentions of Bruce Wayne, but does remove authors with the name Bruce Wayne as well as publications from Batman University in Turkey), or indeed Mary Poppins. The one modern fictional character who seems to defy all the rules is Harry Potter, but that is for another article and a different anniversary.

Figure 2 begs another question that goes beyond Bond: Despite possessing either cult status or serious literary impact, it seems that women are not getting their due as cultural gateways to support narratives in research literature. Searches for Elizabeth Bennet (from Jane Austin’s Pride and Prejudice) produced a mere 1,687 research outputs and Jane Eyre does a little better, being mentioned in almost 12,000 outputs, but Hermione Granger, a significant source of inspiration for many up-and-coming researchers, is mentioned in a mere 562 publications, not yet receiving the same level of success as her literary school friend Harry, despite being the one who does all the research in the books! Anna Karenina has given her name to an “effect”, “bias” or “principle” depending on the field, all of which have made the translation of her brand to the research environment successful.

This lack of reference to female characters from fiction in the research literature is not a surprise. Female characters are just as well drawn as male ones, often more relatable, and hence better suited to performing these key roles in research narrative to help render research itself more relatable. This is a complex sociological issue that deserves more research. At a high level, a simple explanation may be that the male-dominated media of the past is responsible for establishing male characters in the zeitgeist and that a male-dominated research ecosystem (also of the past) is more apt to use male characters to make their points. However, the fact that these practices endure today is something that requires more analysis and attention, at least in the opinion of this author.

Whether or not this is “No time to die” for Bond is not in question from the perspective of research literature. It is, however, clear that references to Bond serve not only narrative or contextual use cases, but invite us instead to ask more challenging questions. In the final analysis, whether he will ultimately die another day or whether he will only live twice are questions only James Bond can answer.

About Dimensions

Part of Digital Science, Dimensions is the largest linked research database and data infrastructure provider, re-imagining research discovery with access to grants, publications, clinical trials, patents and policy documents all in one place. www.dimensions.ai

About the Author

Daniel Hook, CEO | Digital Science

Daniel Hook is CEO of Digital Science, co-founder of Symplectic, a research information management provider, and of the Research on Research Institute (RoRI). A theoretical physicist by training, he continues to do research in his spare time, with visiting positions at Imperial College London and Washington University in St Louis. Daniel could be called the M of Digital Science, but he would like to be the Q – by his own admission, he is definitely no 007.

The post For Scholars’ Eyes Only? appeared first on Digital Science.

from Digital Science https://ift.tt/AhmfGog

No comments:

Post a Comment